On the Revision of Chomsky’s M.A. Thesis

Many historians have noted the abundance of source material on the remarkable career of Noam Chomsky. But, often in the same breath, they have also commented on the tendency of these sources to obscure, rather than clarify, important developments.

Konrad Koerner, for example, has worried that “despite [a] wealth of information, there may be puzzles confronting the historical investigator regarding specific points in Chomsky’s intellectual biography” (Koerner, 2003, p. 2). More recently, Randy Allen Harris has characterized the journey “Into the Great unNoam” as an adventure into “dangerous and enigmatic territory,” one fraught with conflicting take-aways:

He is gracious. He is obstreperous. He shows great compassion. He shows great contempt. He is courageous. He is acrimonious. He works very hard. He is very smart. He is unwaveringly dedicated to the pursuit of ideas generally, fiercely dedicated to the propagation and defense of several specific ideas. He argues congenitally, inexorably, ruthlessly (Harris, 2021, pp. 33, 41).

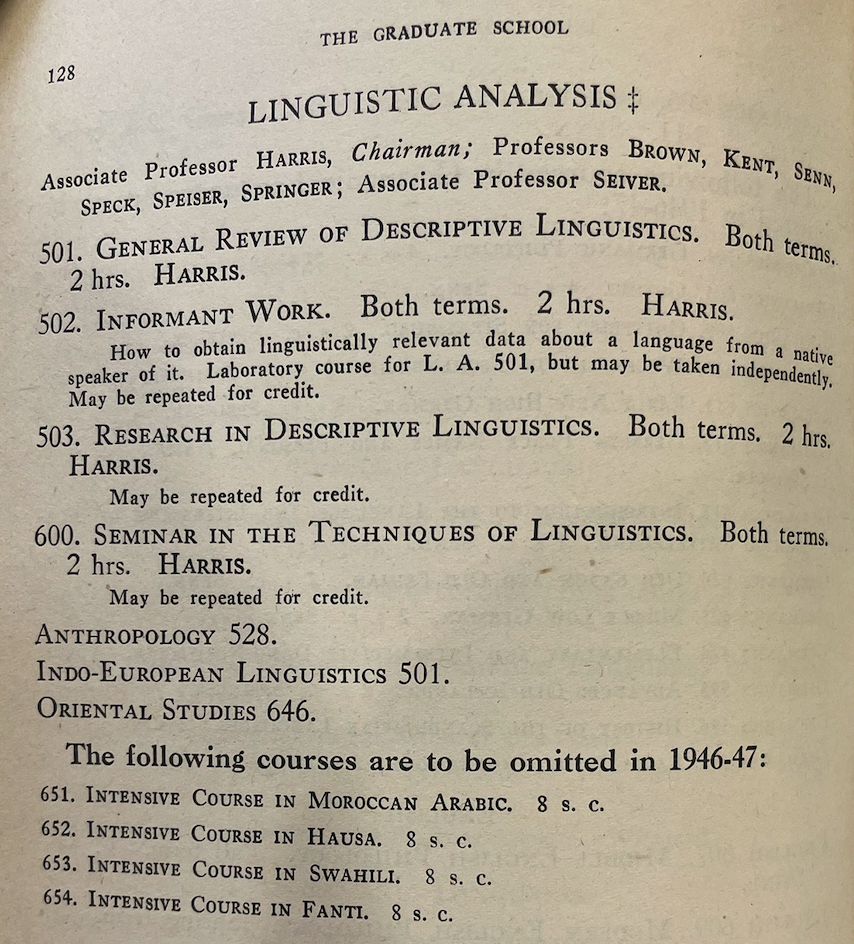

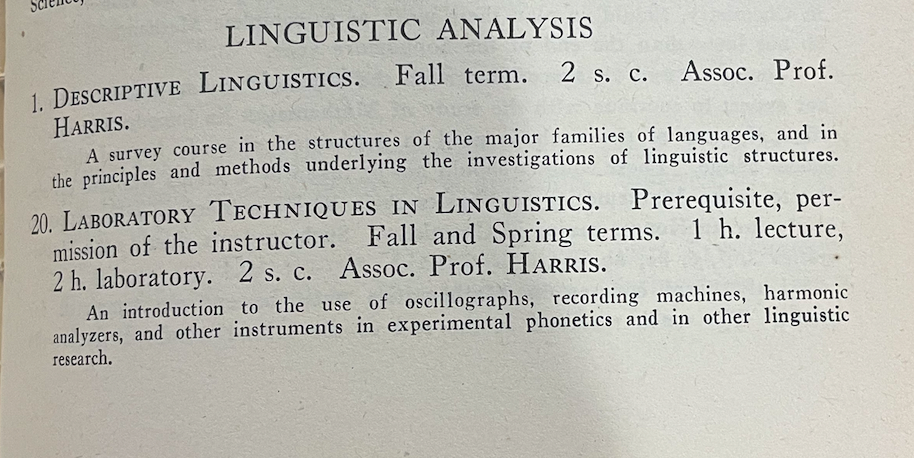

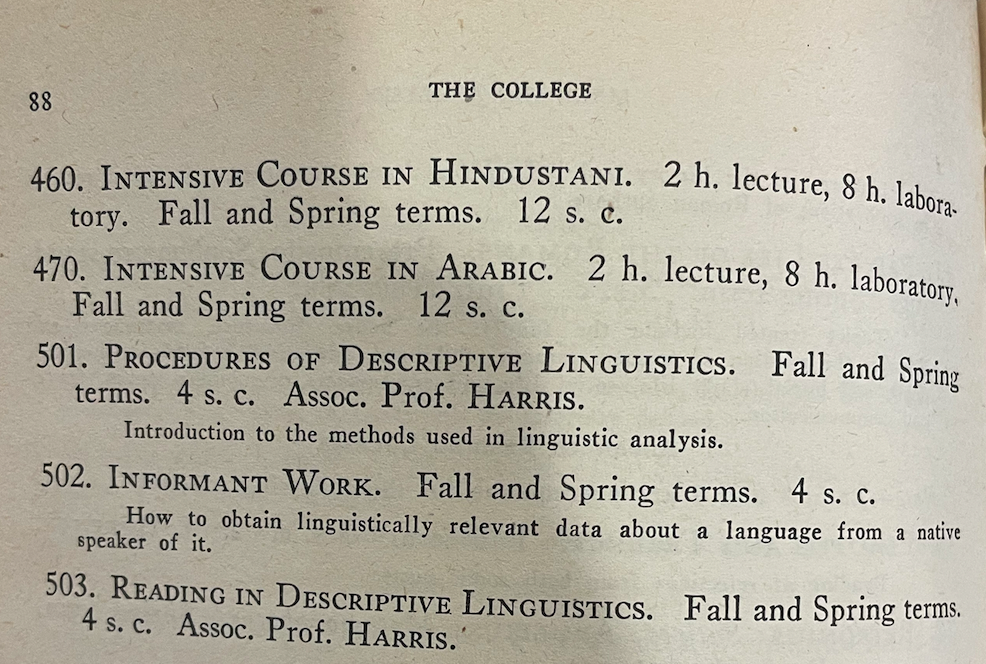

One major puzzle for Koerner and Harris—not to mention, most of the historical investigators and participant observers they discuss—concerns the nature (or existence) of the Chomskyan “revolution.” They test Chomsky’s claim to revolutionary status by the connections he may be shown to have maintained (or painstakingly erased) to the “paradigm” of descriptive linguistics that dominated American linguistics during the first half of the twentieth century. The images below from the University of Pennsylvania Bulletin show how prominent the descriptive approach was in the immediate postwar period. Note that academic year 1946-47 witnessed not only the founding of the program in “Linguistic Analysis” at Penn (by some accounts, making it the oldest department of linguistics in the U.S.), but also the beginning there of Chomsky’s acadmic training in the field.

These course catalogues—pertaining to the Graduate School (top two images) and the College (bottom two images)—are easily accessible in the hallway of the University Archives & Records Center near Penn’s Campus in Philadelphia. As one can see here, Harris took personal responsibility for the vast majority of course offerings. These catalogs also demonstrate the redundancy of undergraduate and graduate courses—both typical of small programs and explanatory with respect to Chomsky’s rapid progress from high school to the M.A. Finally, though beyond the scope of this post, these bulletins attest to a high degree of overlap between the departments of Linguistic Analysis, Anthropology, Indo-European, and Oriental Studies.

This course of study culminated in the production of Chomsky’s 1951 M.A. thesis (theses?) on the Morphophonemics of Modern Hebrew, which has sustained diverse interpretations in the years since it was first published. On one hand, the Morphophonemics of Modern Hebrew has been invoked as a key source for demonstrating the continuity of Chomsky’s early research program with the work of his descriptively-oriented predecessors. On the other, it has been cast as the seed of an entirely new way of doing linguistics—namely, generative grammar.

It is easy enough to access some version of the text: a revision that dates to December 1951 was published in 1979 and reissued as an e-book by Routledge Revivals in 2011. That said, the reissue has a confusing title page that presents it as the June 1951 original (a picture of the original original is given as the thumbnail to this post—it does not mention the month of June). The publisher’s description of the reissue here reinforces the sense that the thesis provides a crucial test of the Chomsky-as-revolutionary idea:

Morphophonemics of Modern Hebrew is a landmark study in linguistics and generative phonology, which provides not only an analysis of morphophonemics but of the entire grammar of Modern Hebrew from syntax to phonology…This work is of singular importance as it contains the genesis of the author’s work in the field of generative grammar which has had such a profound impact upon the study of linguistics. This reissue of a truly pioneering work will be of great interest to all those concerned with generative grammar and its origins, and with the progression of thought of one of the greatest minds of our time.

It is important to note—as Peter Daniels did in 2010—that these two versions of the thesis differ substantially, painting very different pictures of how Chomsky’s thought in fact did progress. Daniels has done a remarkable job of mapping out differences between the two versions with respect to the sample derivations provided (47 in the original vs. 22 in the December revision). He has also provided a very useful transcription of the original introduction, as this was completely excised from the published version that subsequently came to dominate the historiographic debate. This shows, at the very least, Chomsky’s debt to the philosopher Rudolf Carnap and the thoroughgoing efficiency of his editorial process.

With thanks to Daniels and the Kislak Center for Special Collections at Penn, the opening sentences of the original version read as follows:

This study has its roots in two fields, symbolic logic and descriptive linguistics. But the work which constitutes the body of this paper is not an example of what is customarily done in logical construction, nor, for that matter, is it a typical representative of work in descriptive linguistics. In that case, its status remains undetermined. This introductory statement will attempt to explain the status of the present study in Modern Hebrew grammar, exhibiting:

1. The connection of logic and linguistics

2.The connection (or relevance of this paper to logic

3. “ “ “ “ “ “ “ “ linguistics.

Compare this to the opening of the revision that started to circulate six moths later:

A grammar of a language must meet two distinct kinds of criteria of adequacy. On the one hand it must correctly describe the ‘structure’ of the language (i.e., it must isolate the linguistic units, and, in particular, must distinguish and characterize just those utterances which are considered ‘grammatical’ or ‘possible’ by the informant, including as a special subclass those of the analyzed corpus. On the other hand it must meet requirements of adequacy imposed by its special purposes (e.g., pedagogical, as a basis for comparative study, etc.), or, in the case of a linguistic grammar having no such special purposes, requirements of simplicity, economy, compactness, etc…Thus the linguistic analysis of a language L can be described as the process of determining the set of ‘grammatical’ or ‘significant’ sentences of L…or, in other words, it is the process of converting an open set of sentences—the linguist’s incomplete and in general expandable corpus—into a closed set—the set of grammatical sentences—and of characterizing this latter set in some interesting way.

Three main contrasts jump out at me when I read these passages against one another. First, whereas the original acknowledges debts to established literatures (including the descriptive tradition), the tone of the second introduction is much more self-assured. Here, Chomsky tells readers what “must” be the case four times in half as many sentences! Second, the heavy emphasis on grammaticality judgments, which would become central to the generative tradition, is entirely new with the December revision. For those historians seeking to pinpoint the origins of Chomsky’s revolution in linguistics, then, they might want to focus attention on events in the late summer and fall of 1951. Finally, Chomsky introduces logic and linguistics more or less as equals in the original; but he subordinates the “linguist’s incomplete and…expandable corpus” to the logical requirements of “simplicity, economy, compactness, etc.” in the revision, these being inherently more “interesting” than mere description. When these passages are re-read in context, this last point does in fact seem like a gradual “progression of thought.”

Such issues may be highly motivating for linguists who are interested in better understanding where they come from. But for my purposes, the comparison of these two theses is much more valuable as a case study in the construction of collective disciplinary memory. More sources (…interviews, recollections, reissues) does not lead straightforwardly to greater clarity. At some point historians just need to come up with an “interesting” way of characterizing a subset of the ever-growing archive.

Works cited :

Chomsky, Noam. 1951a Morphophonemics of Modern Hebrew. University of Pennsylvania [thesis]; Revised 1951b; First published 1979 by Garland Publishing; Reissued 2011 in the series Routledge Revivials.

Harris, Randy Allen. 2021. The Linguistics Wars: Chomsky, Layoff, and the Battle over Deep Structure, 2nd Edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Koerner, E. F. K.. 2003. “Remarks on the Origins of Morphophonemics in American Structuralist Linguistics.” Language & Communication 23: 1-43.

Nevin, Bruce. 2010. “Noam and Zellig.” In Chomskyan (R)evolutions, Douglass A. Kibbee, ed. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company,